Lessons From the Storm

"All week long we got tips from one another, helped one another."

Welcome to our weekly column offering perspectives on lit mag publishing, with contributions from readers, writers and editors around the world.

When they said to fill the bathtub to have drinking water on hand I thought it was overkill. I didn’t think Helene would make it this far inland. Won’t all the mountains be a deterrence? But what do I know? I’d never been through a hurricane before. It had been raining heavily for a couple of days already in Asheville, North Carolina, and though there hadn’t been any lightning and thunder, which was what I thought would cause a power outage, I filled the tub, and two large soup pots thinking, might as well.

Thursday night as the wind hissed at the windows and rain continued to pour I had visions of water flooding the crawl space and rising through the furnace vents. At four in the morning, we were awoken by the carbon monoxide detectors beeping loudly because the power had gone off. I went around the house lighting candles. We have an electric stove but a gas fireplace. I heated water over it and made my husband a mug of coffee just in time. He was so thankful; he called me a genius. I spent the entire day sitting at my desk watching the rain fly sideways and the wind lash the trees and bushes. A birdie came up to my windowsill under the patio roof and huddled there. My cell phone service died. I couldn’t play my NYT word games. Couldn’t write. Couldn’t read. Just sat and stared.

And then nothing came out of the faucet.

The rain stopped around three in the afternoon. We live on a hill. The grocery store parking lot at the bottom was flooded. That evening we drove into downtown Asheville looking for Wifi and spotted fifty or so people outside the Moxy hotel staring at their phones.

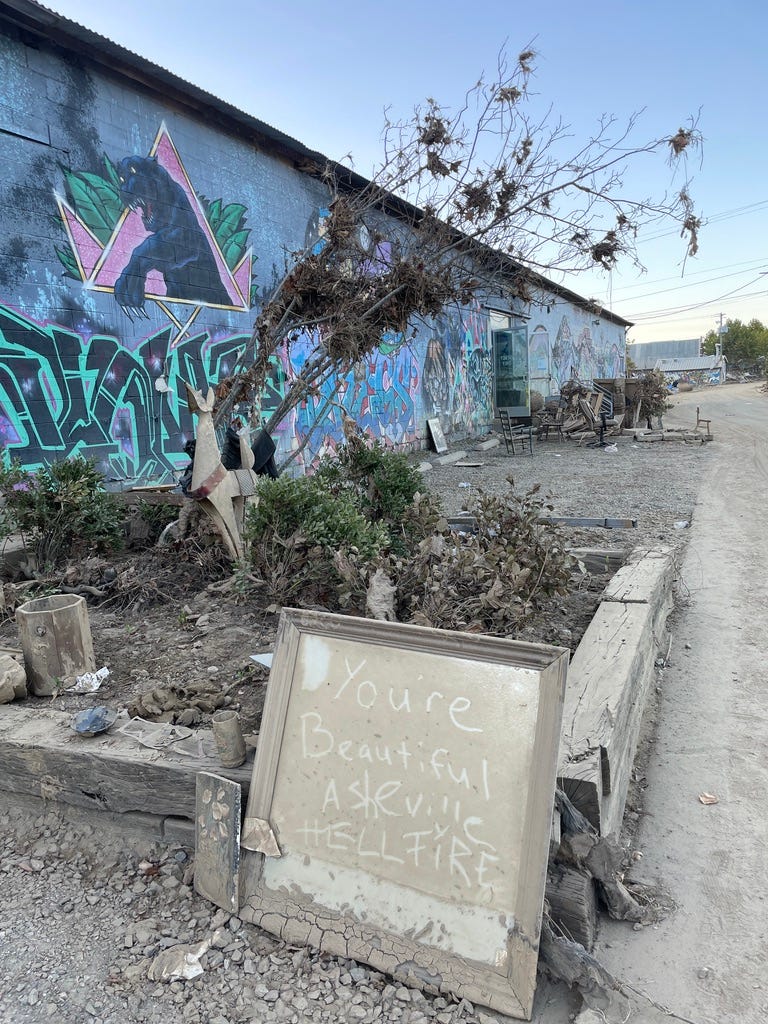

“Must be a hotspot,” my husband said. I hopped out while he waited in the car with the dogs. I was able to text my daughter. She texted back. It felt so good—communication from the outside world. Phone calls still wouldn’t go through. It was 7:25 p.m. A patrol car drove by enforcing a 7:30 p.m. curfew. We had no idea yet of the devastation just a mile west of us. The River Arts District gone. The life’s work of three hundred artists in the mile-long stretch destroyed. Swannanoa. Black Mountain.

By Sunday afternoon, potable water in the soup pots was gone. The water in the old bathtub looked funky. The tub had been painted by previous owners and the coating was coming off, bits of it floating on the surface, but at least we could flush the toilets with it.

Sunday evening, we stood in the water distribution line with five-hundred people, waiting for the supply truck to arrive. I walked and walked to find the end of the line; more people lined up behind us. We chatted pleasantly, exchanging stories. I discovered the woman next to me was a published poet who taught at UNC-Ashevillle. She gave me her business card. (A poet with a business card!) I saw a friend who’d been standing in line for two hours. She needed to use the bathroom. We walked up the hill to my house. “Sorry about the state of the toilet,” I said, but she understood. We were all conserving water.

Monday morning I tried walking around my neighborhood. Roads were blocked by massive trees. Every route I usually took with my dogs was impassable.

We gathered on my neighbor’s lawn, exchanged updates—Harris Teeter grocery store is giving away free ice. The gas station across from Chick-fil-A is open; there’s a long line, but they’ve reserved two pumps for walk-ups with cans. Ace Hardware is open, but they don’t have power, so they can’t refill propane tanks. We’d run out of propane the second night. I was cooking meals on the fireplace. Spilt eggs into the grate. Tried not to use water to clean it up.

Our neighbor gave us a transistor radio. We tuned in for every local news update. My husband was now getting spotty cell service. My sister texted a photo of the River Arts District. It was gone, completely under water. I cried.

From spending so much time with neighbors who moved in two years ago, I learned that one of their daughters plays the flute. I went home, grabbed mine, and we played a duet together. I delivered ice to an elderly couple across the street. I didn’t know he was in the early stages of Alzheimer’s. I met the young couple two houses down. They’d moved in three months earlier and I hadn’t even known. We went over to a different neighbor’s house, just stopped in to say hello and they welcomed us onto their patio. We’d been meaning to do that for three years. The itch to play my NYT games was gone, replaced by this hunger for news and community.

All week long we got tips from one another, helped one another. Someone a few blocks down had syphoned water from a creek behind his house and was running it into the street so people could fill buckets for flushing toilets. My neighbor grilled a massive number of ribs that had thawed and gave them to my husband who gave some to our neighbors. Before we’d been able to get gas, my husband rode his bike to Harris Teeter but couldn’t fit ice bags into the backpack. A woman noticed. “What’s your address? I’ll deliver it for you.” She did. All week everyone was kind, helpful, friendly.

With no power or Internet, I couldn’t work remotely. I tried to read but couldn’t read more than a few sentences before putting the book down. I was too tired to nap. All our energy was spent searching for water, ice, food, listening to updates, talking with friends, with strangers. Anyone. Everyone.

Sirens rang out constantly. With no traffic lights on the busy four lane street two blocks away, drivers were barreling through intersections. Even my husband did that first evening we’d gone looking for Wi-Fi. “Sorry, sorry. I forgot,” he said when I yelled at him. Huge, Army supply airplanes flew overhead. Helicopters crisscrossed the sky.

Friday afternoon, eight days after we lost power, my husband threw open the screen door. “Our power’s back!” The Duke Energy guys were working on the poles at the end of our block as I watched from our front porch. I danced in the front yard, tears trickling down my cheeks, and clapped for the Duke Energy guy driving by in his truck. He saluted and waved. Our cell phone service was restored. We got Internet, though a weak signal, but still. I turned on the TV. I watched the news, saw the horrible devastation. We tuned in a TV show. It was soothing. It felt good.

Afterward, I looked out the kitchen window and saw my neighbors chatting with the young couple on the front lawn. We went over to join them. I didn’t want to lose the connections we’d made the week after Helene destroyed so many lives. But already, something had shifted. We no longer depended on one another to survive.

More than a week has passed now. We’ve all gone back inside our houses. The grocery store down the block has opened. At the checkout counter I was about to leave when I paused and asked the clerk, “How are you doing?” She smiled wearily and said okay. I asked if she had power back and she said yes, but without it, all week her kids had said, “Going out to play, Mom.” But with power and cell service restored, they were once again glued to their phones. “I’m thinking of stealing the modem,” she laughed, but it seemed like she was only half kidding.

I want to remember the lessons of Helene—to get my face out of my screen, to look up and see the person I am facing, to be curious about the stranger before me, a possible friend if I take time to notice, to be present to my community instead of passing through it glued to my phone.

FCC Chair Jessica Rosenworcel spent all week in Asheville to oversee recovery efforts. She said, “In any crisis, communication is a lifeline. We must use this storm to understand ways we can make this infrastructure more resilient and more accessible in the future.”

Yes, of course. But I use this storm to remind me that the lifeline of communication includes talking in person. We can so often feel lost without technology—and we often are. But it all means nothing if in the end we lose the most important thing of all: human connection.

We live in NC but 4 hours east of Asheville. I just told my husband that watching the news only tells half the story but writers, oh writers, get to its heart. Thank you, Polly for sharing your heart.

Great article, thank you. Life changes on a dime, whether a hurricane, a sudden death, , 911, ... our lives are changed. Humility grows as awareness to our necessary and sacred interdependence emerges. and every time this occurs, we are given the great opportunity to remain a little bit more awake, a little bit more compassionate, a little bit more self loving. Like a rubber band, once stretched, never truly returns to its original state. What is most humbling is that often we know what's going on in the world, but fail to know what's going on with our literal neighbors. Yes, your article is heart wrenching, but let's not over look how inspirational it is. Many thanks for your words