This past Monday morning, I received a phone call from my brother. The instant I heard his voice, I knew what he had called to tell me. Our father had passed away.

It had been expected, which in some ways is a kind of blessing. We have not had to deal with shock, on top of everything else. Though there has been shock, plenty of it, over the past ten months. Shock at the sudden decline of my father’s health, shock at the ferocity with which dementia stole him from himself. We were also shocked, many times, by unexpected recoveries, by his strength, his will, the ferocity of the fight he still had inside him.

His stamina shouldn’t have surprised me, though. This was, after all, a guy who drove a taxi in New York City for nearly two decades. He was a man who’d been born into a Jewish ghetto in 1946, in what was then Japan-occupied Shanghai, China. At age two, attempting to leave China for Israel, the British re-routed him and his parents to a refugee camp in Cyprus, where they lived for another year. When he finally came to the US at age 11, he was put into the First Grade because he didn’t speak any English. He would go on to earn a PhD in Film Theory at NYU, and eventually, after retiring from taxi driving, teach high-school English full-time in Bedford Stuyvesant, Brooklyn.

Why am I sharing this here? Well, listen: You’re my community. If you read this ‘Stack, share it, subscribe, leave comments, come to interviews and information sessions, participate in one way or another, then you’re a part of this space. And so I want you to know.

Also, in a weird way, my dad is everywhere here. It feels strange to think that you don’t already know him.

But because most of you never met him, I’ll tell you: He loved writing, he loved teaching, he loved thinking, and he taught me nearly everything I know.

In high school I had an assignment to write a short story. I vividly recall reading that story aloud to him. He didn’t just nod and say, “That’s nice.” We sat at the kitchen table and talked about it for hours. When I grew frustrated, he would say, “Writing is hard. If it was easy, everyone would do it.”

In my early twenties, shortly after college, he was the one who encouraged me to take an adult-ed writing workshop. I’d already had the catalogue for the Cambridge Center for Adult Education. Yet I kept throwing it away. I would read the catalogue, toss it in the recycling bin, take it out, read it again, throw it away, take it out again. Until finally, at my dad’s urging, I went ahead and signed up. That class would be the first of many.

My dad told me to get an MFA. He even offered to pay for it. I wasn’t sure he could actually afford it. Regardless, I declined. I didn’t say it at the time—I didn’t articulate it to myself at time time—but the academic environment is never one where I’ve felt most comfortable. It’s not something I can quite explain, and in truth it’s often led to feelings of insecurity and inadequacy on my part, especially among writers who work so hard and appear to thrive so gracefully in that arena.

Only, maybe now I can explain it, because just recently I think I’ve started to understand. My dad, you see, loved knowledge. He loved philosophy, psychology, etymology, poetry, classical music, Greek mythology. And it was from him, on long car rides in the passenger seat of his taxi cab (the medallion of which he eventually purchased, so he could own the cab) that I learned the foundation for everything.

My dad was the first feminist I ever knew. From him I learned about The Male Gaze, how it plays out in film, in TV, in commercials. He was hugely into the Postmodernists. From him I learned about Foucault, biomedical surveillance, the panopticon. My dad taught me about Jungian archetypes; he explained to me what Freudian psychoanalysis was. There was Marx’s class consciousness, Sartre’s false consciousness. What, we wondered so often, even was consciousness?

He loved the Deconstructionists. For a long time, he was preoccupied with Derrida, with meaning that could not be known because language only deferred to language. Then it was Lacan who captured his attention. For years he spoke of almost nothing but the Real, the Symbolic and the Imaginary.

Lest this paint a picture of someone pontificating in a tweed blazer, know that my dad was also a jokester, a goofball, and that he loved his Hawaiian shirts. I often teased him by asking him what time his shift started at Trader Joe’s.

My dad loved film. You could not rent a movie with him because he had already seen everything, probably twice. Favorite movies: Once Upon a Time in America, which, even in advanced dementia, he could still whistle the music of; Psycho, Vertigo. His dissertation was on Fritz Lang and the German Expressionists. But he also loved the action stuff, Die Hard and Fast and Furious. He watched Goonies with us about seventy million times.

When I was in my final weeks of pregnancy, my dad rented a place near me, so he could be around to help with the baby. My partner and I didn’t have a car, so my dad was who I called at one in the morning to drive us to the hospital. On the way there, as I sat huffing in the backseat, he and my partner got into a conversation about Alien Vs. Predator! They actually sat, parked in front of the hospital, discussing movies! Hello, guys, I’m in fucking labor! I think I shouted at them.

But I digress. On long car rides to visit my grandparents in Connecticut, that’s where I got so much of my education. Or else it would be while watching movies. He would hit pause, rewind to show me what the director was doing, how the camera’s angle revealed a character’s authority or weakness in a scene. How a close-up indicated a character was having an epiphany. He explained how radical it was the first time a director used the device of close-up, then cut, to indicate we were going into a character’s memory. Would audiences be sophisticated enough to understand that this was the character thinking? those early filmmakers had wondered.

In all of this, he taught me about craft. How films and books and art are made, put together through a series of choices. They don’t spring into the world spontaneously. The creator executes choices. Those choices themselves are shaped by factors both known and unknown—the artist’s personal vision, their social location, ideological influence. It’s our job as viewers and consumers to ask why, and to what effect.

I didn’t learn any of this in school. Or maybe, some of it. But most of it, I learned from him. In his taxi cab, in Greek diners, on subway rides to Manhattan, over pizza at Brooklyn’s Pino’s Pizzeria.

So many times, he ruined a great book for me. I once read a passage out loud to him by a famous and acclaimed writer, a writer I adored. He replied, “Statement, metaphor, metaphor. That’s what she’s doing. Her technique is to over-write.”

Once, I read to him three lines of a Rachel Cusk novel. He said, “That writer’s British, isn’t she?” When I asked how he knew, he said, “I can just tell. British writers have a certain style.”

If I didn’t feel the need to get an MFA, I think now it was because for so much of my work, he was my sounding board. I called him, read a passage, he told me where I’d made missteps. I went to revise. Called him back thirty minutes later. Read it again. More missteps. More revision. More phone calls. Never once did he say he was tired or bored.

Instead he said things like:

You need more conflict. The conflict is the river of your story. You have to keep dipping the reader’s toe into that river.

Or,

The ending of the story needs to resolve the premises laid out in the story’s opening. What are its premises?

Or,

Go darker. Why are you afraid to go dark? GO DARKER!

I was not the only one he taught. At his high school, when it was clear his students were not reading 1984 as was assigned, he had them forget about the homework and together they read each page out loud in class. So they would get it. Really get it.

Later, he brought in an audio recording so the students could hear it being read. He said the students were entranced.

At some point he decided to scrap lesson plans altogether and use pop culture to teach Greek mythology. Did you know The Golden Girls exemplified the Goddesses Athena, Hera and Aphrodite? Ever think about how it was the same Greek-goddess triad in Sex and the City?

He went entirely rogue to teach them The Odyssey. He was convinced that if you went through each moment, line by line, teenagers would love it. He was always in trouble for not teaching to the Regents exams. It didn’t matter. He hated standardized testing. He wanted his students to have an actual education.

My mother, who taught Adult Literacy, also in Bedford Stuyvesant, once told me my father’s name coincidentally came up in conversation with one of her students. The student told her, “Oh yeah. Mr. Tuch. He was the only one who ever taught me anything.”

My dad loved this newsletter. He, too, had aspirations of writing fiction, publishing it. He always said he needed to get better at submitting his work.

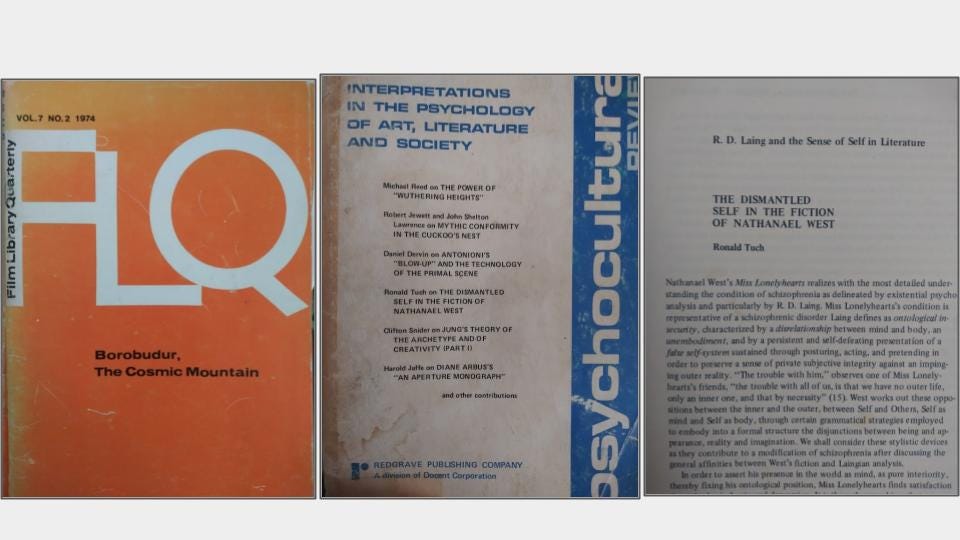

Up until two days ago, I’d thought he had not really published much. But then, going through his apartment, I found old journals from the 70s with his articles in them.

This week, as my partner and I discussed arrangements, he asked me if I knew whether my father wanted to be buried or cremated. In response, I burst into laughter. Maybe it was the sleep-deprivation. Maybe it was a kind of panicky hysteria. An inability to face what my dad always said that Lacan always called The Real.

Or maybe, the reason I was laughing is that I know the truth. The truth is, it is impossible. In a literal sense, yes, okay, fine. The physical body ends. This we understand. But in another way, my dad will be neither buried nor burned, not ever.

He cannot be. He is everywhere. In my writing, in my love for craft. In my love for teaching, my passion for doing what I can to help other writers. Every time I get into a taxi. Every time I remember diagramming sentences. Each time the previews come on in a movie theater. In that moment when I watch a film and understand it is visual language I am interpreting, or when I critically appraise something because the creator didn’t see their own ideological contradictions, or when I watch a commercial and recognize every visual ploy being used to sell and manipulate.

Or, in the case with literature, when I read slow as a sloth, because I have to read every sentence three times, asking how it was put together, why it was put together in this way, what effect it has on me, why it has this effect, so that every single work comes to contain the world, and I know that every piece of writing, no matter the perceived quality, offers something important and worth thinking about.

My dad is here, in the way I think. In the fact that I think. In the pleasure I take in solitude. In the joy of company. In my love for getting others to talk and debate and discuss and ask and explore. In all the ways I joke around with you, dear readers (Trickster archetype!). In all the ways I’m serious about this work (Athena archetype!). In all my efforts to share this craft and nurture a community of fellow writers, teachers, learners, askers of questions, seekers of answers.

So, thank you all for letting me tell you something about my dad. He will be missed more than I can even comprehend. But also, he is here, he is here.

And he is also here.

What a beautiful tribute to an extraordinary man. You are so lucky to have had him, and you carry him in your humor, your grace, your strong sense of community, and your bold, powerful prose.

Becky, I am moved to tears at this gorgeous and heartfelt tribute to your father, which I read today on my own father's Yahrtzeit. I think we all feel honored that you have shared your father with us in this way and I'm sure I'm not the only one who wishes we had a teacher like him when we were in high school. I hope you'll keep writing about him. May his memory be for a blessing.