Let's Discuss! North American Review, Fall 2022, Vol 307, #3

Lit Mag Reading Club discussion

Welcome to our Lit Mag Reading Club discussion!

So? What did you think of North American Review?

I’ll be honest. I had never read any part of this lit mag before. According to its site, North American Review was “[f]ounded in Boston in 1815” and “is the oldest and one of the most culturally significant literary magazines in the United States.”

I did know the magazine’s history. As a result, to be honest again, I expected something that was a bit more, I don’t know, aesthetically conservative? Conventional? Maybe even a little stuffy?

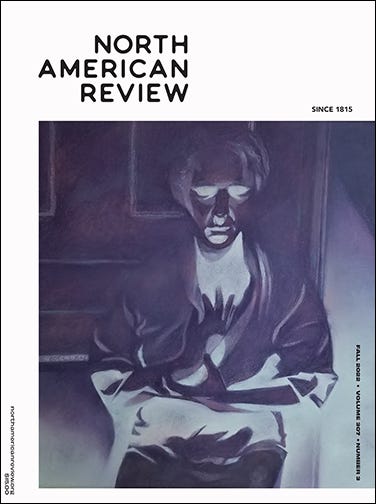

Much to my absolute delight, the journal is anything but. This was immediately evident when the issue arrived in the mail, showing up in unusually large shape and size, with strange, haunting artwork enticing me to look within and explore.

The theme of this issue is Spiritualism, which might be a nod to the Transcendentalist writers who published in its pages way back when. Or—and this is how I took it—a welcome invitation to explore alternative realities during a time when so much of our day-to-day realities present such hardships and challenges. In these pages you will find seances, mediums, “orb photography,” “skin writing,” kitchen cupboards that cause spontaneous bleeding, ghosts, “transfiguration,” superstition, and, for lack of more critical terminology, some really cool, far-out stuff. There are also searingly personal essays, moving poems, historical short stories, and a few works that are exquisitely absurd and funny.

This issue contains 5 short stories, 7 nonfiction pieces, and works from 35 poets and 11 visual artists. There is a fair share of heavy material, including death of a parent, death in childbirth, domestic violence, school shootings, stillborn babies, strokes and sickness. Fittingly, there is also a charged, visually dense and emotionally gutting poem by Julie Marie Wade entitled “What is a Trigger Warning?”

Contributors to this issue are a mix of writers with one to one dozen books under their belts as well as those with just a few publication credits or for whom this is a first-ever publication.

So many of the pieces here resonated with me. Notable poems include Anemone Beaulier’s “A Sexual History: How Do You Protect Against Unplanned Pregnancy?,” which explores unknown and unintended consequences of birth control, and perhaps the speaker’s regrets of youth more generally.

My youth diminished, desire chemically dampened: I chose that and didn't know I'd chosen.

Samantha Padgett’s “I’m Told the Speaker in My Poems Lacks Growth” delves into the writing process and examines the burden placed upon poets and this poet in particular—“to crack open my body…to reach elbow deep into my chest” in order to reveal a depth of suffering.

In Naomi Kanakia’s “Relive,” the speaker is watching someone, likely a child, “as you reach for the garbage truck,” while also pondering life’s mysteries and the speaker’s conflicting desires, struggles and regrets.

The mind is made for cocaine, not these subtle, fleeting joys.

Martín Espada’s series of poems tie personal family history with political history, address police brutality—“There were cries, then silence. There were no last words,” and pay tribute to Eugene Povirk who passed away last year and who, according to his obituary “started his own used book business specializing in labor and social reform.” Espada writes:

…I made my pilgrimage to see you, a sage in the mountains, cloistered in his cave of books, the words of Eugene V. Debs on a sign nailed up over the doorway in your shop. With a flashlight, I would squeeze in the stacks, bookshelf after bookshelf of dead rabblerousers and hellraisers, strikers and muckrakers, poets and socialists, words stirring in the darkness...

Among the nonfiction, I was particularly wowed by Laura Bernstein-Machlay’s “Needle Life.” This piece uses a recurring needle to knit together aspects of sickness, family and motherhood. It opens with a memory of the narrator’s grandmother teaching the narrator’s child self to thread a needle. But what might at first appear to be a quaint childhood reflection quickly takes on a darker overtone as the needle pricks the narrator and she “showed…my punctured thumb.”

The piece weaves in the narrator’s own daughter, that daughter’s early trips to the doctor, the child’s subsequent fear of needles, later mother-daughter trips to get ears, then belly button, then septum piercings, and various surgeries and medical interventions where a needle played a central role. “In the throes of childbirth, for instance, the needle came to me as a celebration. The long needle that slid like cool water into my spine and ended the agony of Celia wrenching her full self into the world.”

At the end of the piece, the narrator addresses her daughter directly, writing that she would readily “take all the world’s jabs that will break your skin and your heart,” and she would “be cushion and thread and needle all, so you’d always have a soft place to land, always have the means for stitching yourself whole.”

Given the heaviness of this issue overall, the absurdity and humor found in some places was an especial joy. Will Ejzak’s “Dads Like White Elephants” is about a young woman who is convinced that her dad disappeared when she was a child and another man returned in his place, and that no one in her family is willing to acknowledge what happened.

There is a sadness at the heart of this piece, and also a mystery. Is the narrator in denial about a larger trauma she experienced as a child? Did the father actually abandon them all? Are there larger secrets the rest of the family is unwilling to address? Some of that is resolved at the end, when we learn of the father’s deceitful behavior. But not all the questions are answered, nor need they be. It is quite enough to indulge this narrator’s wild perceptions and go along on her ride.

Part of what makes the story so engaging are metaphors of violence and grotesqueness strewn throughout otherwise generic experiences such as first dates and family gatherings. They are pitch-perfect as far as metaphors go, while also lending insight into the narrator’s flights of fancy and the tremendously high stakes she feels regarding interactions with her family. At the Christmas party, “Beneath the tree, presents lay scattered and abandoned like corpses on a Civil War battlefield;” “Outside of the living room, the house felt weirdly abandoned, like the place had been evacuated moments before a nuclear strike;” “Flickering candles on the dining room table drooled into their holders. In the kitchen, a nearly perfect apple pie sat on the counter; someone had cut out geometrically exact eighth, and the apple innards oozed into the vacuum it had left behind.”

The story’s ending features a fainting grandmother, a fireplace fiasco, an escaped ferret named Ferris, spilled orange soda, a crying child, David Bowie, actor Ewan McGregor, an ambulance, a death, and eventual acceptance of the seemingly impossible. What could in clumsier hands veer into slapstick or goofy satire in this case comes together to deliver wondrous surprises and satisfaction.

Tony Zitta’s short story “Losing Everything is Like” is also about a young person grappling with a parent’s disappearance. This piece, however, is much bleaker in tone and subject matter, though there are occasional flashes of wry humor and insight.

Here, Anthony is told to come to the hospital to say goodbye to his mother, who is dying of a brain tumor. Only, his mother does not die. She recovers from surgery, then commits to a healthier lifestyle while also refusing the chemotherapy recommended to her. Anthony is disoriented by this— “[N]o one told me she would be different. No one said she would wander free. No one said she would think medicine was a lie…She ate ginger root, organic carrots, and dandelion salad saying that she was cured.”

As the story unfolds we learn that part of the narrator’s detachment from the entire experience—the way he returns from the hospital and casually eats chicken nuggets, burps, watches TV, half-listens to his grandmother—has to do with his alienation from his mother and a kind of numbness that has settled in. As a child she often made him feel unwanted, drank heavily, and verbally and physically abused him. The story’s title refers to the George Michael song, in which he “sing[s] about how losing everything is like the sun going down on him,” and how as a boy Anthony had watched his mother cry “like she also lost everything.”

Eventually, the mother’s tumor returns and it is inoperable. They return to the hospital, this time “into a special room with electric candles and cushioned seats.” What happens at the end of the story might feel too wrenching for some readers. Personally, I found there to be a raw beauty here, a necessary telling of what happens in these final moments. In fact, I wish more stories would cover this territory, laying out the bare details of what is so often difficult to talk about.

Zitta writes, “In the moments leading up to when we die, there is paperwork. And there are plenty of people helping to explain what happens sext. They are confident. They really seem to know.”

But what can be known, really? Various physical processes are explained to Anthony—the body’s “natural process of slowing down all its functions…;” how “[p]eople who are dying often sleep a lot.” There will be a loss of control over bodily functions, changes in breathing, cooling of the skin, and so on.

Still, what can be known about this experience? What can be known about the soul, if you believe in that sort of thing, the spirit, the essence of a person, where it begins and where it ends and where it goes?

We don’t find answers in this story, as Anthony makes a small and devastating blunder at the end. But are such questions even answerable at all?

For that, perhaps, this is where we must turn to our spiritual guides, those who have connections to higher forces, those who communicate with something beyond this realm and who might share with us their knowledge. For that, we have this issue of North American Review.

There is, of course, so much more on offer here. But now I will turn it over to you.

What did you think?

What moved you?

What made you wonder, think, laugh, question, dream, consider?

What surprised you?

How did you find the physical layout of the journal?

How did you see the works speaking to one another?

Let’s talk all about it!

We will be speaking with North American Review Editor J.D. Schraffenberger on Tuesday, February 28th at 1:30 pm est. If you have not yet done so, you can register to join the conversation here.

I, too, was surprised by the spiritualism -- but drawn in. The Séance photographs were eerie and evocative. I liked how some of the other selections -- Ghosted, Chaldea -- carried the theme. I thought Chaldea, in particular, had a Nathaniel Hawthorne vibe -- fitting for this issue on supernatural experiences.

I ordered a copy but not yet got it did pull out a fall 2021 copy a beautiful and aesthetic presentation has a nice feel nice size to it looking forward to the interview.