Let's Discuss! Southern Review, Fall 2022

LIT MAG READING CLUB Discussion of Southern Review

Welcome to our Lit Mag Reading Club discussion!

I began this issue at the end, my attention immediately piqued by the title of Terence Winch’s poem, “JFK, Assassinated.” The poem is uncannily timely as last month saw the release of much-awaited and long-withheld CIA documents pertaining to the president’s murder.

Of course, anyone looking to get to the bottom of this incident once and for all will not achieve that goal here (nor in the documents, for that matter). Winch’s poem is not about the CIA. Nor is it about the mafia, the government, Oliver Stone, Lee Harvey Oswald, Abraham Zapruder, Cuba, Russia, secret societies, hitmen, or any combination thereof. It’s not even really a poem about the president.

“JFK, Assassinated” is a poem about the poet’s own personal history, where he was at the moment news of the assassination broke. But it’s also a poem about a more general history, a time that was simpler in some ways and more brutal in others. “Life…was cold and golden.”

While the lack of historical analysis might be a disappointment to some (or a relief, depending on your turn of mind), the poem does in fact offer historical insight. Perhaps the biggest insight is how much in common we all share, across generations. One does not need to have experienced JFK’s assassination personally to appreciate the way shocking crises beget a profound and collective loss of innocence.

Who among us hasn’t yearned for a time of pre-crisis, a time when

You could go our very late and night and walk the streets

smoking cigarettes, looking for love. You could stay until

the bars closed…

You could sit on the stoop, blowing smoke

at the sky, wondering what would happen, you know, in

the future, which was like a far-off country…?

This issue of Southern Review contains twenty-seven poets, seven short stories, one nonfiction piece, one art portfolio, and one crossword puzzle (!). Contributors cover a broad span of experience, including some writers with only a handful of publishing credits and others with multiple books. The issue also includes translations from major writers, including the Romantic-period German poet Friedrich Hölderlin and essayist, novelist, editor and winner of Italy’s most prestigious literary prize, Guiseppe Pontiggia.

Beginning with the end of this issue and moving backwards is, as it turns out, a perfectly suitable way to go through the content. Much of the work here deals with personal reflection, the sort of nostalgia captured by Winch, or else a looking backward toward one’s roots.

In “North Alabama Poem” Rodney Jones reflects on his past and his grandparents. Jones writes, “Oh story of Alabama…story it takes three women and one old man to tell…My story grows from biblical and folk rootstocks. It impedes the ever-encroaching money economy, for no payment can occur without an exchange also of stories.”

Leona Sevick’s “Dilettante” tells of a person who, while walking home from work, hears the crack of a baseball bat and is sent into reminiscence of “a time when/ all you wanted was to sit your/ ass on the cold metal bleachers/ and watch your boy play baseball,” and then to a time before that, the speaker’s own childhood and lost dreams.

Michael Meyerhopper’s “What My Grandmother Taught Me” looks tenderly at life lessons passed down to a grandchild. “If you have animals, feed them/ all your table scraps—wheat crusts/ soaked in grease and gravy…Remember me/ if it’s not too much of a hassle.”

Philip Schultz recalls in “School Buses” the end of a day at school “when the accordion doors opened on all our mothers aunts older sisters/ and grandmothers waiting maybe since the Peloponnesian Wars/ to welcome us back into the whirling jubilant unwieldy splendor/ of their arms…”

In “God Made Dirt, & Dirt Ain’t Popeyes” Bernardo Wade writes of “churned milk, which may have tasted/ a little sour, like childhood—or like/ a yearning to crawl back inside/ a simpler time…”

Nostalgia is not the only theme here. There is also death, aging and finding the beauty in small mundane moments. There are also trees. And flowers. A lot of trees and a lot of flowers.

The nature imagery might be a bit much, were it not for the variation offered by each new encounter. These are not only trees and flowers after all. They are windows into a variety of individuals’ states of mind. As such, they are copious but also varied. Through each new lens these trees and flowers become something beautiful, comforting, haunting, dangerous, powerful or politically charged, depending who is doing the looking.

Taije Silverman’s “The Delta” begins with “The dark gold bark of the crape myrtle” which “curves like the arms of Ine’s younger daughter/ who pushes a stroller past roots that have ruptured…”

Yasmine Amelies’s “Bedtime Story (8)” is a story of the poet’s mother, who “will birth me, name me Yasmine, my jasmine flower” and who “will show me how to check a jasmine plant’s soil for dryness…will let me fill the watering can under the tap.”

In “Retold” Leona Sevick writes, “Do you see these fired daylilies? Their velvet, /tangerine heads held up by long, strong necks? Note/ the tiny, clenched fists of the mountain laurel,/ the purple, swollen fingers of wild orchids…”

Terence Winch’s additional poems feature “Fallen World” where “You never cry anymore. /The trees don’t make/ you weep” and “The Open Door,” in which “One day the trees will raise their arms up/ as you walk by. But that will just be me/ saying hello…”

Both Gary Fincke and Olivia Clare Friedman’s poems tell harrowing stories about boys lost in the woods. In “Missing: A Psalm” Fincke describes a boy’s near-kidnapping in breathtaking lines that reveal near-disaster at every turn:

Had the boy, such a smart five-year-old, not unlocked the door and walked away.

Had his mother not been bedridden by fever in their upstairs, rented rooms.

Had the boy, for half an hour, not bounced a rubber ball off a vacant building.

Had his aunt not arrived to nurse her sister and noticed, at once, his absence…

Friedman’s “Finding Him” follows Fincke’s with

…The story of

the little boy who fell

in the forest. They found him

that way, among the crisscrossing oaks

all the living things, scurrying

around him. He’d been there

for some time, having

walked out the front door, entirely

on his own…

In “This Pattern” Albert Goldbarth features both flowers and trees, the latter which serve as a metaphor for our country’s seemingly endless and irreconcilable political divides:

Eventually

the election signs get pulled away,

and the front lawn flowers—just look at them!—

are visible again,

emerged as if from an eclipse.

I’ve often watched how here on Echo Street

the trees on both sides…

lean, at their highest,

toward the center of the street,

and meet there, blending indistinguishably,

and make a single canopy,

and make it look to our human stares

as if it were fucking easy.

Was this issue of Southern Review specifically dedicated to nature themes? Were certain works accepted for this issue once it appeared particular motifs were organically recurring? Or do a lot of poets just so happen to write about flowers and trees?

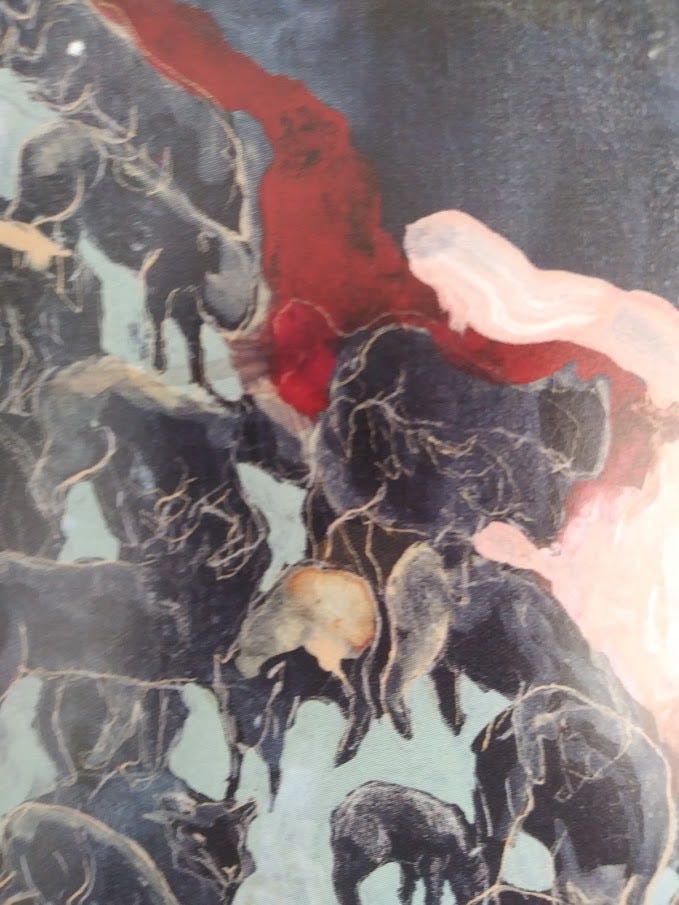

There’s no editorial letter to guide us on this front. What we do have is stunning cover art from Amber Jensen and her portfolio of gorgeous drawings. Yes, here again, we encounter trees and flowers. But there is a darkness lurking within these images that intrigues, pushing beyond being merely pretty and toward something deliciously haunting. (Though, with their rainbow palette and delicate lines, they are indeed extremely pretty.)

In “the new little lambs” a cluster of animals mill about on a mountainside. But a deeper look reveals how the bodies overlap one another, how they appear to be translucent. It is quite possible that these precious lambs might in fact be ghosts. The image only darkens once one takes into account the heavy flood of white-pink and blood-red that flows down on top of them.

In spite of what’s mentioned above, this entire issue of Southern Review is not exclusively nature-focused. Apart from Michael Griffith’s playful and delightful crossword puzzle and “Hink Pinks” word game, it is the fiction and nonfiction that most deviates from this motif.

Bryn Chancellor’s “Remnants” is a moving story about a young woman trying to overcome opioid addiction and heal from the wounds inflicted by an abusive mother. Corbin Muck’s “A Centennial History of Cascade Depths National Park,” is the most structurally experimental piece here, alternating between court documents, written history and straight narration to tell the story of a contested piece of land.

“The Naming of the Partners” is a short and exquisite piece by Giuseppe Pontiggia, translated by Linda Worrell. Here Pontiggia dives into the nitty gritty of the workplace, in this case a firm where a man has just learned that he will not make partner and likely never will.

It begins, “Today, the naming of the partners. My hopes, finished. My trust, deceived, and now for the last time.” The story is set in one single scene, though the piece speaks volumes about rivalry, ambition, and “the unrelenting struggle to get ahead, which on days like today triggers so many awkward, ridiculous behaviors.”

As the story goes on, we are introduced to the other characters who did make partner—“the pint-sized Coletti with the squeaky voice;” “Ghezzi, who is huge and fat, almost bovine.” In fact, all of the narrator’s co-workers “are extremely short.” Yet in spite of their physical size, these men will reach the heights for which the narrator longs, and they will thrive. At the end a fellow coworker delivers painful truth: “In this place, connections are the only things that count….Blockheaads are the ones who float; all the rest are heavy, they sink.”

The story feels a bit undeveloped, a slice of life perhaps more than a fully realized narrative with rising action and character transformation. One wonders whether an unknown writer might find a home for a similar story in such a prestigious literary magazine. No matter, the piece offers funny and poignant insights into the workplace while, like any good translation, whetting an American reader’s appetite for more work by this foreign writer.

Emily Mitchell’s “The Church of Divine Electricity” is a refreshing jolt of sci-fi-esque narrative not often seen in mainstream lit mags. Here we encounter Henry and Carol, parents of Rebecca. There is nothing especially extraordinary about this family. Henry and Carol are contentedly married, live a comfortable life in the suburbs and have just sent their only child off to college. Henry (the point-of-view character) is relieved to see that Rebecca has overcome a phase of adolescent rebellion that would set her on an irreversible path of self-destruction.

Only, when Rebecca visits home one week, Henry can’t help but wonder whether she may be acting a bit too good? A bit too pleasant and cooperative? He doesn’t want to push his luck and ask prying questions. But what is he to make of her newly cheerful demeanor and then the strange blessing he glimpses his daughter making over their meal?

As it turns out, Rebecca has joined a new religious order. “Singularism,” Henry learns online, “was founded by a man called Semyon Brink, a software developer and futurologist, to be ‘a spiritual movement for the information age.’ Its core belief is that humans are destined to transcend our bodies through technology. Singularists believe this transformation will be coming very soon. Their purpose is to hasten it.”

Henry is disturbed, though he tries not to panic. That is, until he attends a Singularist meeting with Rebecca and witnesses for himself the technological “enhancements” that members have voluntarily added to their bodies. He sees “a woman whose legs below the knees are two elegant metal wands; a man whose skin over his face and neck is bluish and hardened, like the rind of some alien fruit; another man has convex lenses over both eyes in which patterns of colored light flex and dance.”

The story is perfectly timely in its look at technology, the human body and the merging of the two. Questions abound regarding these issues, most recently in the art and literary worlds’ concerns with artificial intelligence and creative works. We also see these questions arise regarding new Twitter owner Elon Musk’s embrace of transhumanism and his visions for Neuralink, the neurotechnology company that could seek to provide the human brain with the functionality of computers.

And yet, at its core, Mitchell’s story is a timeless one, with human questions that feel just as pressing as the societal ones, if not more so. How much should a parent interfere with a child’s chosen path? How much can a parent interfere, without pushing that child away? How do parents navigate this world where our children are daily exposed to so many ideas and changes that are beyond our control? How do we protect them? How do we let them go? And how far are we willing to go to keep them safe?

Great questions. A great story.

And part of a great package overall.

What did you think, dear readers?

There are poems and stories I did not mention here, or could not go into more deeply for lack of space here and reading time. So please, tell me, what spoke to you? What did I miss?

What was educational, interesting, exciting?

What inspired you, made you think, made you reflect?

What did you enjoy?

Please don’t be shy to weigh in! I want to hear what you think! Even if you only read one story, one essay or poem. What did you think of it?

Thoughtful criticism is also welcome. But please keep it constructive. Don’t say anything you wouldn’t say to a writer in a workshop with you.

Thanks for being the thoughtful, engaged, understanding and passionate readers and writers you are.

We will be speaking with editor Sacha Idell on Thursday, January 26th at 12pm est. All are invited to attend and ask questions. The video will be made available for anyone who can’t attend in person. Register here.

"The story feels a bit undeveloped, a slice of life perhaps more than a fully realized narrative with rising action and character transformation."

And yet this is far from the universal model for short fiction, so it's notable that this is a story in translation from a contemporary Italian writer.

But this, yes: "One wonders whether an unknown writer might find a home for a similar story in such a prestigious literary magazine." A similar question arises when we consider what might be made of work by some canonical poets and writers of fiction if, thanks to time travel, it could be shown in unpublished form to a contemporary MFA workshop.

The image of the women waiting for the bus "since the Pellepensian (sp?) Wars" Made me want to kiss the poet.