Literary Criticism as a Secular Spiritual Discipline

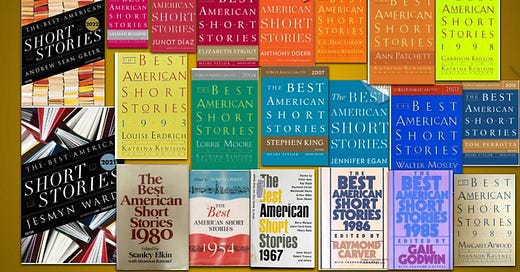

Writer discusses his project to read and review every story in Best American Short Stories each year.

Welcome to our weekly column offering perspectives on lit mag publishing, with contributions from readers, writers and editors around the world.

“When you were a child you believed yourself special, deserving, and every piece of evidence to the contrary broke your heart. As an adult, the same was true.”

- Elizabeth McCracken, “Mistress Mickle All at Sea”Literature has always been psychologically linked with religion for me. When I first realized I wanted to “do something with literature” in my life, I was twenty-three and starting to realize I didn’t believe in the evangelical Christianity I’d entered early adulthood with. This was happening while I was slogging through a five-month stint on board a ship in the middle of the Pacific Ocean during my last two years in the Marine Corps.

One of the reasons I’d been hesitant to completely abandon my faith was that I didn’t know what could take its place. For no particular reason, I’d taken a copy of Moby Dick on board. It was one of those books I believed people should read at some point, and while on a boat seemed like that point. Somewhere in the middle of one of Ahab’s monologues, perhaps the “Quarterdeck” chapter, I realized that literature was probably the best I was going to be able to do as a replacement.

Because of this association, I probably don’t read literature the way most people do. I certainly don’t read it the way most professors do, with a very theory-forward reading. That’s one reason I quit the study of literature after my M.A. instead of continuing on to make literature my full-time profession. I look to literature to help me figure out the answers to big, existential questions. There is nothing theoretical to me about these questions; I’m literally asking stories questions like, Why should anyone not immediately end their existence in a world that seems to make no sense?

I took to literature to help me decide what decisions to make, to craft my own meaning of right and wrong, even if I no longer believe in capital R Right and capital W Wrong. Not only do most literary scholars not seem to think this is the point of reading, but most writers would deny that they even want any such responsibility. Nonetheless, it’s the role I’ve given them.

Of course, the texts of modern short stories and novels aren’t made of the same stuff as religious texts. You won’t get a “thou shalt” in a Curtis Sittenfeld story, but in the best stories there is wisdom to read, to chew over (“meditate upon,” to use the religious discipline term) and to either make a part of you or to wrestle against.

The closest analogy between reading literature and religion, I’ve found, comes with the act of criticism. Criticism forces me as a reader to develop not just a keen mind, but qualities that could be described as spiritual ones—discernment, humility, graciousness, and grace (the last two being different in important ways despite their status as cognates).

When I say “criticism,” I mean “thinking seriously about the meaning of a story on a number of levels and writing about it.” There’s a difference between the terms literary review, literary criticism, and literary theory, but for me, I don’t feel the need to distinguish much between them.

Since I’m not a professional literary practitioner, I’m not writing articles for journals that will be picked over by other professionals, who will then write articles of their own either agreeing with or arguing against me. (A second reason I abandoned literature as a profession after the M.A.: realizing the goal of scholarship seemed to amount to propagating endless discourse, none of which aimed to ever come to a semi-authoritative resolution.) Literary criticism to me is a public act of spiritually interacting with a story.

I write for a blog. I’m not even smart enough, like the editor of this blog is, to figure out how to use Substack. I’m still using Blogspot, which is now so old in the tooth, it’s a wonder anyone finds me at all. Some readers do find me, though, and when they do, it’s almost always for a piece of criticism I’ve done. For the past five years, I’ve blogged on every short story in Best American Short Stories. I’ve also done a few blog-throughs of Pushcart and the O. Henry anthology. I figure it’s a useful niche for someone like me, a guy who’s had more literary training than the average Joe but not as much as a professional.

Literary criticism to me is a public act of spiritually interacting with a story.

Professionals tend to write for other professionals, whereas I hope to be more of a bridge between professionals and thoughtful working people who, like me, do something else for a living. (“Bridge builder” is the original meaning of pontifex, a term for a high priest.) Because there is so little serious writing for the public about short stories, I feel like this is something useful I can do. It’s my form of “literary citizenship,” to use a term I’m not entirely sure should exist. It’s very clear from the few comments that show up on the blog that most readers are students dabbling in the waters of short stories looking for a little help understanding what they’re reading. That means I get to be a teacher without going to any faculty meetings. Not a bad hobby.

There’s a bit of a responsibility that comes with this, though. For a lot of these students, I assume they’ve read a story in BASS or another anthology, found it difficult, and Googled it. Often, the top results are the story itself, followed by either my blog or Karen Carlson’s. They’ll probably pick one of us, both if they’re really ambitious. (Often, Karen and I refer readers to one another, so some of her readers come from me and some of mine come from her.) That means that I’m one of maybe two voices these readers are ever going to hear about these stories. For the writers involved, it could mean picking up a few extra readers, which is always important in a profession that doesn’t pay much.

I have a responsibility to the writers to consider their work seriously. I have a responsibility to readers of my blog to review the works honestly and thoughtfully. I also have a responsibility to myself to review the works with a full and open heart, because the point of reading has always been what the purpose of religion is for some people--to develop into a person who is capable of fulfilling gradually higher purposes in the world.

I have a responsibility to the writers to consider their work seriously…I also have a responsibility to myself to review the works with a full and open heart.

Blocking me from fulfilling these responsibilities are the usual deadly sins, not the least of which is sloth. Looking back a few years to just before I’d undertaken to write more thoughtfully about short stories, I see that I commented on Karen’s blog in 2017 about how an Elizabeth McCracken short story somehow didn’t do it for me. Since writing more seriously about short stories, however, McCracken has become possibly my favorite contemporary writer. I just re-read the story (“Mistress Mickle All at Sea,” the one quoted in the epigraph), and I found it to be equal to any of the other great work she’s done. I found it, in fact, to be the equal of almost anything I’ve ever read. What was I thinking in 2017? Most likely, I was simply reading too casually.

When a writer offers a story, it’s an invitation to intimacy. Rushing through it is akin to rushing through sex. Someone is offering you a valuable part of themselves. That doesn’t mean you have to like it, but it does mean you shouldn’t treat it like it’s nothing just because you want to get through blogging all twenty stories in an anthology by the end of the year. That’s why I always make myself read every story twice before I write a word about them.

A much greater stumbling block than sloth, though, is envy. I am never more than a two-second trigger away from hating everyone who’s accomplished more as a writer than I have. (In keeping with the religious imagery, I think confession can be important for literary minds.) It’s not that I’ve never had any success with my own fiction (really! Look at this good thing that happened to me and this one), but I am a guy who once dreamed on a ship of being Melville and now works a job he’d prefer not to do but can't quit and isn’t anywhere near being able to make a living out of writing. (So…kind of like Melville.)

This year, while blogging through BASS, I had to review a story from a writer who’d been in the same edition of the same journal I’d been in. I felt envy. During an aborted blog-through of Pushcart, I was dealing with the fact that I’d been nominated (maybe…the editor said she wasn’t sure she’d gotten the nominations in on time, because the journal had moved), but not selected. Again, I felt envy. I felt like the specialness of the stories I was reading made me less special. Maybe better people than me don’t feel this way, but it’s hard—to maintain the sexual metaphor—to not feel that I’ve offered intimacy to someone and been rejected in favor of others.

I am not describing here what should be. I’m telling you what is, the real feelings I struggle with. I’m sure actual religious clergy struggle with something similar— “I’m way more humble and faithful than that preacher, why does he get all the congregants?” There are so many ways envy could color my reading. The obvious one is that I’d be too resistant to a story, but it’s also hard not to be so afraid that I’m being negative out of envy that I end up being overly positive. (Or worse still, to be so afraid of people thinking I’m envious that I give an overly positive review.)

Envy makes it hard to be sure of myself that I’m being genuine. There’s also the concern in my head that a negative critical reading could affect my chances of being published myself one day. Since most readers of short stories are themselves writers, I assume that’s one reason there is so little serious criticism available to the general public about short stories. It’s too risky for most readers. There’s a reason Karen and I are near the top of those Google results.

To say that poems are prayers is now so common as to be somewhat hackneyed. (A poet I know Tweeted an attempt to update this with the pithy but somewhat unconvincing edit that poems aren’t prayers, but rather why we pray.) If poets can bend religious imagery toward secular texts in this way, then I think it’s not too bold to think of literary criticism as a type of sacrament, a ceremony or ritual one does in order to connect more fully with the divine.

In the Quaker tradition, they do not speak so much of sacraments as of disciplines, such as fasting, meditation, prayer, and quiet. I think of writing criticism in this way. With a discipline, it isn’t necessary for us to be in a completely perfect mindset before we start. The point of a discipline is to do it, and in the process, the right mindset will sometimes come. Do the disciplines enough, and eventually you’ll be in the right mindset more often. Wrestle with sloth and envy through criticism, and maybe, one day, you’ll have just a little bit more control over these things all the time.

And here I arrive at an ending that can only be called evangelical, in the sense that I am spreading the good news about writing thoughtful pieces about literature online. While on the one hand it’s nice that my little, aesthetically challenged blog occasionally gets some readers, what this is really a sign of is how anemic the critical community of American literary fiction is. Karen and I should not be the only people blogging through BASS, but we seem to be. And that’s BASS, the one short story anthology that probably gets more love and attention than any other. How much less attention do the smaller anthologies get, let alone individual journals? I’m sure every writer out there who’s ever been published has dealt with the crashing realization the day after their story comes out that nobody cares.

We often talk about the glut of good writers from all the MFA programs and all the good advice that’s available freely now. We talk about how there aren’t enough readers for all these writers. We probably can’t do much about these things, but we can do something right now to slightly increase the amount of thoughtful readership in proportion to the amount of thoughtful writing. You can do it right now. You can read any journal, find one thing that appeals to you, and keep thinking about it until you have something interesting to say. I’m not talking about some quick Twitter post that says, “Emma Cline’s latest is <fire emoji>.” I mean write something that costs you some sweat.

Post it somewhere. Tag the writer some place. (If your criticism is harsh, and you’re sure it’s really what you think, of course, it’s fair to post it, but for God’s sake, don’t tag the writer.) Maybe the writer never sees it, or if they see it, maybe they never respond, but I guarantee you there are thousands of writers out there whose week it would make to have one person respond to their creative act of love with a reciprocal critical act of love. The only apt word to describe this completion of the literary cycle is “consummation.”

This is so beautiful. Ok I will do it.

I find this piece downright inspiring and important in wide ways