Welcome to our weekly column offering perspectives on lit mag publishing, with contributions from readers, writers and editors around the world.

Contemporary writers are more than familiar with navigating the cultural minefield that is the modern literary scene. But what would happen today if a writer tried to subvert a particular style of poetry by fooling a significant publisher into taking seriously a work that parodies that style? Thereby hangs this true tale that includes an obscenity trial and the CIA along the way.

US, Canadian and UK writers may find it difficult to imagine that an Australian culture war would become a cause célèbre that would echo around the world of modern poetry. However, in 1943, that’s exactly what unfolded in the burgeoning shoot-out between traditional and modernist poetry.

Two conservative Australian poets, James McAuley and Harold Stewart, were appalled by the modernist art and literary movement and decided to make its proponents a laughing stock by hoaxing them. They created a fictitious poet, called Ern Malley, and wrote sixteen pieces in one weekend of what they regarded as complete nonsense under his name. They then had Ern’s equally fictitious sister, Ethel, discover them after Ern’s tragic early death and mail them to a leading modernist poetry magazine in Adelaide, South Australia.

Why did they do it? They said it was because modernist poetry

“represent(s) an Australian outcrop of a literary fashion which has become prominent in England and America. The distinctive feature of the fashion, it seemed to us, was that it rendered its devotees insensible of absurdity and incapable of ordinary discrimination. Our feeling was that by processes of critical self-delusion and mutual admiration, the perpetrators of this humourless nonsense had managed to pass it off on would-be intellectuals and Bohemians, both here and abroad, as great poetry. ..”

So, how were Ern’s poems constructed? McAuley and Stewart sat down with a range of books open, including books of quotations, rhyming dictionaries, scientific papers and even Shakespeare, selected lines at random, made up new words, and strung them together to produce such gems as this from his poem “Petit Testament:”

There is a moment when the pelvis

Explodes like a grenade. I

Who have lived in the shadow that each act

Casts on the next act now emerge

As loyal as the thistle that in session

Puffs its full seed upon the indicative air.

I have split the infinite. Beyond is anything.

Or this, from “Documentary Film:”

The elephant motifs contorted on admonitory walls,

The subtle nagas that raise the cobra hood

And hiss in the white masterful face.

What are these mirk channels of the flesh

That now sweep me from

The blood-dripping hirsute maw of night’s other temple

Down through the helpless row of bonzes

Till peace suddenly comes.

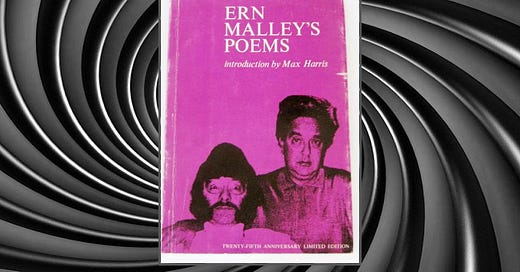

When Max Harris, the 21-year-old editor of the magazine Angry Penguins received Ern’s poems, he was enthralled and excited by the work of someone who he perceived was a literary genius who, like Keats, had died tragically young. So, in 1944, he decided to devote an entire issue of the magazine to Ern’s work, calling the collected poems The Darkening Ecliptic.

Shortly afterwards, the hoax was revealed in the newspapers, resulting in the humiliation of Max Harris and the severe setting back of the modernist poetry scene in Australia. Worse was to follow when the local Police decided some of the poems were obscene and Harris was fined 5 pounds (around A$250 now) for publishing them. Angry Penguins folded in 1946.

Normally, all of this would have become a footnote in Australian literary history and unknown to the broader world of literature outside the Antipodes. But along came the 1960s and Ern was discovered by leading American poets John Ashbery (he even wrote a few poems in Ern’s “voice”) and Kenneth Koch and, later, Ted Hughes.

Part of Ern’s revival was the insistence of some critics, including Robert Hughes, that McAuley and Stewart had accidentally created great poetry in the process of parody. Hughes said “The energy of invention that McAuley and Stewart brought to their concoction of Ern Malley created an icon of literary value.”

Max Harris defended to the end the quality of the poems and had a successful career as a bookseller and newspaper columnist.

McAuley later converted to Catholicism and became a vehement anti-communist to the point that the CIA funded the establishment of his magazine, Quadrant, in 1956. He died in 1976. Stewart became a Buddhist and moved to Japan where he wrote haiku. He died in 1995, the same year as Max Harris.

Of course the ultimate irony is that they are all outlived by a man who never existed. And in his poem “Sybilline,” that is exactly what he predicted.

It is necessary to understand

That a poet may not exist, that his writings

Are the incomplete circle and straight drop

Of a question mark

And yet I know I shall be raised up

On the vertical banners of praise.

Great post - fun and informative historic dive

I love it! As a poet myself, I want to be understood, to use vivid language and metaphors that everyone can understand. I teach poetry. I am appalled at some contemporary poetry that prides itself on being difficult to understand and "fresh" and "new". Give me Robert Frost, Elizabeth Bishop, Billy Collins, Adrienne Rich, Dorianne Laux and dozens of others, whose language enriches the heart and touches the soul.