Why Heresy Press? Why Now?

Upon one-year anniversary, Heresy Press Publisher looks at the press's role in the publishing landscape

Welcome to our weekly column offering perspectives on lit mag publishing, with contributions from readers, writers and editors around the world.

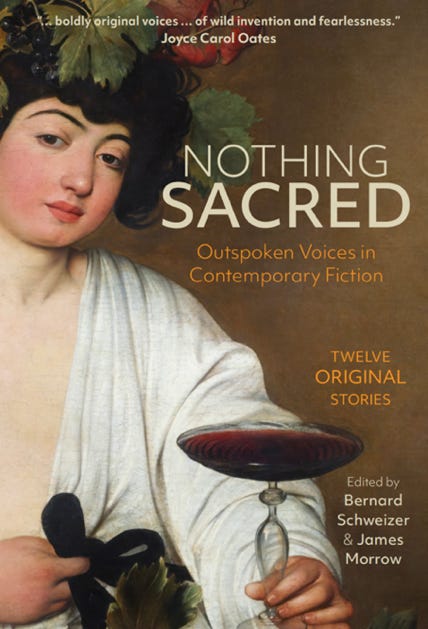

Press founded: January 2023 Submissions received to date: 215 in total (85 short stories, 130 full-length novels) Accepted manuscripts: 12 short stories, 4 novels Rejections sent: 124 (73 short story rejections; 51 novel rejections) Pending manuscripts: 75 (novels) Published to date: 1 book (Nothing Sacred: Outspoken Voices in Contemporary Fiction) To be published by summer 2024: 4 novels (Deadpan; The Hermit; Animal; Unsettled States)

Background:

Heresy Press was founded one year ago in response to a profoundly unsettling state of affairs in literary publishing. Many authors felt increasingly alienated, disrespected, and bewildered because the rules of the game had abruptly changed without them being consulted about it. Long-held assumptions that acceptance into the literary fold was based primarily on demonstrations of literary merit (imaginative originality, superior style, narrative skill, etc.) seemed suddenly to have lost their legitimacy. In their place, a new set of rules began to take hold of the publishing world wherein an author’s identity was inexorably intertwined with evaluation of the work itself. Traceable to 2015, when the movement identified by the hashtag #OwnVoices took off, this change has since drastically redefined what literature is at its core.

Motivated by the justified need to diversify publishing, which for too long had been a bastion of white and mostly male networks of preferment, promotion, and advantage, #OwnVoices offered a deceptively simple panacea to the perceived racial, ethnic, and gender imbalance in the literary world: Authors with backgrounds presumed to be privileged should not be allowed to graze on pastures belonging to marginalized identities, while members of minority groups were strongly encouraged to write about their own struggles and experiences.

Faced with massive online agitation and galvanized by identity politics, literary agents and publishers willingly hopped on the #OwnVoices bandwagon, intent on signaling that they were on board with the idea of diversifying the literary marketplace and eager to promote underprivileged perspectives. But the law of unintended consequences soon kicked in, and what began as a well-intentioned initiative in favor of diversity, progress, and openness turned into an instrument of exclusion, restriction, and soft censorship.

As PEN America’s extensive report “Booklash” documents in exasperating detail, #OwnVoices led to a dramatic narrowing of literary freedom while setting out identity traps for both white and non-white voices, compelling them to sing only from a short and narrowly prescriptive songbook. Instead of being regarded as visionaries capable of imagining worlds beyond their readers’ ken, writers were now asked to prioritize the art of navel-gazing while simultaneously navigating a thicket of proliferating (informally enforced) taboos and prohibitions.

What began as a well-intentioned initiative in favor of diversity, progress, and openness turned into an instrument of exclusion, restriction, and soft censorship.

Existential threats often come in twos, and this situation is no exception. A creative writer negotiating the treacherous waters of the publishing process is nowadays faced with two different threats: on the left shore looms the hectoring specter of cultural appropriation, an eagle-eyed bird of sensitivity perched on its shoulder, ready to swoop down on perceived instances of offensive language. On the other shore squats the lumbering monster of book-banning, ready to squash any book whose subject matter doesn’t align with its own value system.

The idea (represented by the phantom on the left) that literature must be well-behaved, non-offensive, didactic, inclusive and above all restricted to the perspective seemingly best representing the author’s own identity markers is patently absurd to true artists. Likewise, the attitude purveyed by the monster on the right, i.e. that literature must not endorse (or appear to endorse) the “wrong” values so as to avoid corrupting delicate readers, is scarcely less galling to writers. Hemmed in by these twin threats, scores of authors began to lose hope that they would ever be able to practice their calling unhindered. Am I exaggerating? Only metaphorically so.

What writers tell us:

Since opening our doors, I’ve had plenty of opportunity to take the current temperature of the publishing industry and to feel the pulse of authors who approached Heresy Press as their last refuge. Interestingly, the left-progressive specter of “soft censorship” is perceived as much more serious threat in its effect on creativity than the coarse book-banning monster on the right. Among the countless expressions of disgust over the current situation in publishing that I’ve received from writers since opening for business, 99% were directed against the threats to creative freedom issuing from the enforcers of rigid appropriation-and-sensitivity standards.

This makes sense. Book banning takes effect once books have already made it past the editorial offices and through the printing press, venturing out to libraries, bookstores, and the public square; if anything, book banning may directly boost the sales of a title, lending them the cachet of forbidden fruit. By comparison, the Damocles sword of cultural appropriation and sensitivity exerts a more insidious and subtle influence, prompting writers to veer on the side of safety, to self-censor, and to regress to the mean. As one National Book Award winner put it in an email to me: “I wonder if I'm being too safe in my current work—if I've subconsciously assimilated safety into my work.”

If there is a common thread to the many expressions of solidarity with the mission of Heresy Press, it’s the authors’ conviction that identity politics is ruining literature for everybody, including both writers of all backgrounds and readers of a resilient and adventurous mindset. Here’s one representative example of this sentiment.

Something really strange is going on in publishing now. And it isn't just that White people aren't allowed to write stories that include characters who aren't White. If you look at the Manuscript Wishlist, there are agents that declare up front that they're only interested in representing people who match their race or sexuality. I don't understand how this can be legal in the United States, but more than that, it's a crazy business plan for agents and publishers to be choosing clients based on this criteria. - Obren B.

I’ve heard variations on this theme dozens of times, and usually the laments are linked with gratitude that an outfit like Heresy Press exists to buck the trend:

An established New York agent read a synopsis of [my novel]. “This is the sort of novel publishers are clamoring for,” she wrote in response…. But in the end the agent passed on the novel because of the “insurmountable cultural resistance in publishing” to authors writing in the voice or from the point of view of “characters of a race different from their own.” I’m impressed to discover that your press is willing to brave such “cultural resistance,” provided of course that a particular work of fiction tells a good story worthy of publication. - Martha P.

This last point is crucial. Just as a story is not bad simply because it violates the dictates of #OwnVoices, likewise a story is not automatically superior because it dares to flaunt its “cultural appropriation.” The criteria need to be rigorously literary and artistic, as outlined in the mission of Heresy Press: “Our ultimate commitment is to enduring quality standards, i.e. literary merit, originality, relevance, courage, humor, and aesthetic appeal.”

This quality-driven approach is what appeals to many authors: When I asked Jonathan Stone, whose “Eulogy” is published in our short story anthology Nothing Sacred, why this tale is particularly suitable for Heresy Press, he answered: “Because it’s particularly unsuitable for anywhere else! For ‘Eulogy,’ it was either Heresy, or my hard drive forever. I’m so pleased–and not a little surprised–that this gets to see the light of day.”

Similar expressions of appreciation are trickling in on a regular basis:

“I am very excited about your venture. To me the very best books take chances, liberties, steal, outrage, move.” - Mark P.

“I just want to say thank you for reestablishing courage in publishing. I’ve experienced (forget rejection) a lot of explicit, vocalized (and unnecessary) discrimination from agents. So, thank you again. Much needed!” - Jonathan E.

“I applaud Heresy Press, a voice in the cultural wilderness.” - Trudy H.

Lest it sounds overly self-congratulatory, please keep in mind that these are the voices of writers, and what they are expressing is a real hunger for something that appears to be missing in today’s publishing landscape. Meanwhile, as a for-profit publisher, we cannot power our business with the fuel of authorial gratitude alone, but will need to garner the support and loyalty of a sizable customer base in order to be viable. We will have really made it only when expressions of gratitude and joy are felt also from readers everywhere.

Lessons learned in our first year:

• When I started this press one year ago, I was quite anxious whether we would be able to source enough quality submissions to sustain a well-stocked publishing pipeline. It turns out that that was the least of my problems. So many people are dying to tell their stories that we’re faced with a veritable inflation of fiction. The glut of unassigned manuscripts could give rise to a feeling that there are more writers out there than readers. This situation is particularly pronounced at Heresy Press since our mission is to cater to all writers, including the sidelined and silenced ones.

Given that I am the driving force of this enterprise, with only a few volunteer editors standing by, I had to institute a rigorous editorial procedure or risk drowning under pending submissions. The three-step editorial procedure that helps me clear my deck goes like this: The first step is “triage,” where I read the submitted writing sample (ca. 20 pages) and then either reject it–based on criteria of writing skill, imaginative vivacity, and thematic appeal–or I invite the full manuscript (less than 20% of submitters are invited to send the full text). Next, I read deeply into the full manuscript, and if it still holds up, I then send it out for an external review. Based on both an in-house reading of the full manuscript and on the advice of the external reader(s), the decision is then made to offer a contract or not.

The proverbial slush pile has a dubious reputation, but I actually enjoy diving into it—there’s just no telling what gems you might unearth among the average or even painfully drab fare. The lesson is that great writing rises to the surface of its own accord; it doesn’t need to be pushed, it doesn’t require pleading, and it certainly doesn’t rely on pitches garnished with superlatives.

The proverbial slush pile has a dubious reputation, but I actually enjoy diving into it—there’s just no telling what gems you might unearth…

• Our acceptance rate hovers around that of Harvard’s undergraduate admissions, which is to say that we are extremely selective. And just like Harvard’s admissions committee, we are both making and dashing dreams in the process. This frankly takes an emotional toll on me because being an author myself, I know how hard it is to absorb rejections. Sending rejections to authors who wholeheartedly support the mission of Heresy Press is particularly difficult, and my heart breaks a little every time I need to do this. But it has to be done because for authors there’s only one thing worse than receiving a rejection, and that is not hearing back at all, i.e. silence, which sadly is often the default among mainstream publishers and agents.

• “Who’s the reader for that book?” is a question I’ve often fielded, usually from industry experts. But it is not a question I have a ready answer for because identifying your specific reader is basically another way of playing the game of identity politics. Conventional publishers, both big and small, are operating under the assumption that books are written by a person of identity X, featuring characters of identity X, aimed at readers of the same identity X. In other words, a Black gay author is writing about Black gay characters for Black gay readers. A white female straight woman is writing about …. you get the idea—silos as far as the eye can see.

For instance, who is the audience of Heresy Press’s forthcoming novel The Hermit, Katerina Grishakova’s multi-layered, wistful portrait of a Wall Street bond trader chafing against the rules of his profession? Is it white middle-aged finance bros, duplicating the protagonist? Is it female Russian immigrants, duplicating the author’s background? Is it 7-figure earning New Yorkers addicted to heroin? If you start playing this game, you have already lost. Instead, it’s better to just put out the books and fire your publicity engines up on all cylinders, then let readers of any description find your book. By trying to narrowly pitch you book to one specific audience, you are likely losing potential readers that you haven’t thought of.

• I found out the hard way that anthologies of original stories are challenging and expensive to produce if one aims for a high level of editorial oversight and literary excellence. Moreover, creating cover art for a short story anthology can be a nightmare. Anthologies as diverse and eclectic as Nothing Sacred cannot easily be reduced to a common visual denominator, thus making the job of designing a cover exceedingly hard. We went through dozens of drafts and engaged four different designers before finally settling on the current cover with Caravaggio’s rendition of Bacchus, proffering a goblet of intoxicating liquid. Not only was it expensive to generate so many failed attempts, but it also robbed me of my sleep many a night. In the end, all the trouble and near-heartbreak were worth it, though—the book looks splendid.

• Authors appreciate strong editorial guidance. At Heresy Press, we practice rigorous, involved, and dynamic editorial leadership, including compressing, re-ordering, and re-writing passages. We push authors hard, while remaining open if an author pushes back with good reason.

In a market awash with hastily produced and sometimes shoddily edited books, one way to stand out from the pack is to offer the public an impeccably edited and flawlessly produced book. Most authors are wise to recognize a strong editorial hand as an expression of support, wisdom, and priceless professional guidance. I am an experienced academic editor, with numerous edited collections under my belt, but literary editing required a different skill set. Luckily, I was able to collaborate with James Morrow, a master stylist and extremely meticulous editor, and the lessons I learned while co-editing Nothing Sacred are paying dividends every single day.

• A wholly unexpected lesson is that the quality of work submitted by agents is not any higher on average than the work of authors who submit directly. In fact, it might even be lower on average. Some work coming from agents was so poorly edited, error-ridden, or banal, that it made me wonder what the agent had seen in the story to begin with. What this tells me is that as a general rule literary agents cannot be trusted as arbiters of literary taste and judges of artistic excellence. It also tells me that the big publishing houses who never accept unagented submissions are losing out. They voluntarily cut themselves out from perhaps the most ingenious, fresh, and daring pool of work.

The big publishing houses who never accept unagented submissions are losing out. They voluntarily cut themselves out from perhaps the most ingenious, fresh, and daring pool of work.

• Another note on literary quality: I’ve been confirmed in my view that work written to an agenda is almost always inferior. It doesn’t matter if the agenda is left-progressive or conservative, pro-this or anti-that. If the writer writes in her synopsis that the story is written to “drive a stake through the heart of white supremacy” or to pillory the “excessive tolerance for hard-drugs and crime in progressive cities” or to expose the “silliness of corporate DEI workshops,” the story is almost always going to be inferior. I yet have to find an agenda-driven narrative that is outstanding—it seems an impossibility or rather a contradiction in terms. And that’s why Heresy Press doesn’t insist that submissions must be heretical in some straight-forward or explicit way. That would be just another prescription encouraging agenda-oriented work. Instead, we simply ask that a story be brilliantly conceived, originally written, and freely imagined—the rest will take care of itself.

We take pride in being an industry disruptor and a source of literary inspiration. Our intent is to built a tribe of freedom-loving, resilient, and adventurous readers who are willing to join hands with our equally uninhibited and fearless writers. I hope you will be among the members of this colorful tribe.

This is the first I hear of you.

Your 'mission statement" celebrating your first anniversary is very heartening. I definitely fall into the category of writers who do not fit the current criteria: senior, white, Jewish, left-leaning and female, to name just a few liabities. Thank you for giving me hope!

For some reason, we humans have trouble handling Truth-- with a capital 't' to distinguish it from what the propagandists/ideologues/ fanatics promote as 'truth'. Bernard has nailed this distinction, and I applaud Heresy Press and all those who believe in actual freedom, which must always begin with freedom of thought, as in free will. If this cancel mentality had been in control since written history began, we would never have had Homer, Chaucer, Shakespeare, Melville., Dickens, Mark Twain, Tolstoy, Kafka, Hemingway, and thousands of others who wrote about races, ethnic groups, classes, sexes, etc. they were never part of. Nor would exist the Bible, the Koran, the Buddhist and Hindu writings, or poets like Emily Dickinson, Walt Whitman and William Blake who wrote of God and the soul.

And that may be why great writing becomes immortal--because it is FROM and ABOUT the immortal part of every human being who has ever lived in this mortal world.