"Literature as a Force of Spontaneous Dark Power." A Chat With Lev Parker, Editor of A Void

Editor of Surrealist lit mag takes us into his world

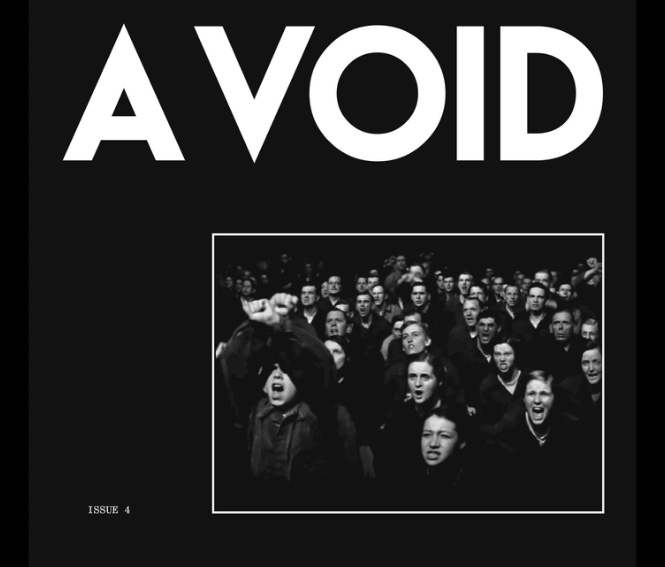

It’s not every day that a literary agent from London reaches out to me, suggesting lit mag editors I should interview. But that’s precisely what happened with Lev Parker. Of course, I’d already been familiar with his journal, as A Void occupies a unique place in our literary landscape. One could say the journal stands in open opposition to the dominant trends in contemporary lit mag culture.

From the Editor’s Note of Issue One: “To paraphrase Tolstoy, each literary magazine stinks in its own way, although there are some startling consistencies between all the titles, which makes our job of vaulting them all in one go easier than it should be…While we don’t like didactic or propagandist poems, we wanted to create a magazine that aids the emancipation of thought from the doctrine of liberal capitalism that other poetry magazines explicitly or implicitly propagandise.”

For our conversation, Lev declined a video interview but he’s open to conversing with anyone with questions about his magazine. Here we chat about the history of A Void, Surrealism, OuLiPo constraints and why the literary scene can be a drag. If you have questions for Lev, please feel free to drop them below.

What is the origin of A Void? How did it begin?

By 2017 I’d quit my job in journalism to write poetry on the streets as a “Poet for Hire” and discovered there were no literary magazines interested in publishing the automatic texts I produced, and none that had a philosophy or aesthetic that was appropriate to my mode of expression, which falls under the category Breton assigned to his seminal anthology, Black Humor. So I decided to start my own magazine and enlisted the graphic-design maestro Penny Metal to make a document that represented my vision of literature as a force of spontaneous dark power.

The journal is described as a “magazine of mass hysteria.” Does this refer to the latest issue, or do you see the magazine as a whole as addressing “mass hysteria?”

The current issue only. The others are variously titled the magazines of “morbid arts”, “new irrational perspectives,” and the porno special, “discipline and pleasure.”

Why a magazine dedicated to mass hysteria? Why now?

Covid sent everyone a little crazy, although the hysteria was already latent in the culture wars.

Stylistically, your magazine embraces Surrealism. In terms of subject matter, works in the latest issue address mass surveillance, class struggle, state power and propaganda. Do you see Surrealism as a uniquely suited form to address these issues? In other words, what is the relationship between the form of your magazine and the content?

Surrealism means literally to go above realism. Whether the realism you perceive is capitalist, socialist, or some other totalitarian abstraction, Surrealism is the simplest and most enjoyable way of elevating your consciousness.

Another theme of the magazine is transgression. Do you think artworks (film, poetry, painting) still have the power to be transgressive, or have we moved past that possibility?

Of course art can still be transgressive. Perhaps the more important question is transgressive of what? And for what reason? I like what David Foster Wallace has to say about the matter in his “E Unibus Pluram” essay, although many of the writers who have taken up his mantle of sincerity-as-rebellion have been co-opted into a culture war that he would almost certainly find nauseatingly sanctimonious and spiteful.

Who are some writers/poets/visual artists whose work captures the spirit of your magazine?

Myself. And of course our eternal leader, André Breton. I guess the overall design is somewhat inspired by the futurists and 1960s avant-garde concrete poetry, but there are so many references that are always changing according to what suits the contents, usually stuff that’s so obscure I feel confident I can rip it off without anybody noticing.

What is the “Temple of Surrealism”?

The Temple is a state of mind. If you’re having trouble accessing it, we recommend joining our Patreon mailing list to receive the materials, which point you in the direction of a fully surreal mindset. Note: it is absolutely not a cult, a swindle or a mental illness.

I like what you say about Surrealism being “the simplest and most enjoyable way of elevating your consciousness.” Do you write down your dreams? Do you find dreams to be fertile territory for accessing an alternative state for surrealist writing?

Poetry is a kind of waking dream. That’s all you need.

What would you suggest to writers who are reading this and thinking this sounds cool, but wouldn’t know how to begin trying to write in this way?

We just ran a residential course in Norway taught by myself and Nina Power where we guided new recruits through the Surrealist writing process, from cut-ups to automatic writing and OuLiPo constraints, using the material from our Mind Deprogramming reading list, which contained everything from Burroughs and Bataille to the Unabomber manifesto, Christian mysticism and the Psychick Bible. It was a mind-opening experience for everyone including myself, although I was never in any doubt that people could produce great poetry if we gave them the correct tools. We’re about to send the anthology to print, and should be announcing the next retreat soon. Members of our Patreon mailing list get priority booking.

What is your editorial process? Do you work with your writers to edit pieces?

I’m a libertarian dictator. Collaborators are free to conform to my standards however they choose. If they choose wrong, I’ll either chuck it out or work with them until we’re both happy with it. But generally, I like to emphasize what people are good at rather than be prohibitive and negative with my criticism. That’s what MFAs are for, they’re all about telling you what not to do, and that’s why so much of the work that comes out of them is quite soulless.

What kinds of submissions do you reject? What makes something inappropriate for your magazine?

A lot of editors bitch and moan about receiving the material they actively solicit, which is emblematic of the privilege and narcissism that pervades literary culture. It’s not exactly “busy bragging,” but it’s related. Is there even a word for it, when you feel the need to complain about getting the thing you asked for? Whatever. Here’s an idea, folks: if you don’t want to read unpublished poetry or short stories, nobody’s forcing you to be an editor of the Backwoods Literary Review, or wherever you happen to be nurturing your ambition of working at the New Yorker. So either fulfill your duty and enjoy what little influence you have with respect for the writers without whom your job wouldn’t exist, or go suck dick in a gas station – which is probably more profitable and rewarding. It’s your choice! Stop complaining.

On the other hand, I never solicit material from anyone other than our members or a few select individuals, so I feel like I’m within my rights to object when writers I’ve never heard of approach me with some thinly veiled bullshit about how much they like my work when they have clearly never read it, in the hope that I will expend my resources promoting them. To create a deterrent, I recently hired my friend’s six-year-old daughter to write personalized rejection letters to the low-level con artists who approach me pretending they’re big fans, when in reality they’ve sent the same thing to fifteen other magazines. My friend’s daughter Elsa has such wonderful penmanship, she decorates the rejection letters with unicorns, rainbows and other marvels. They’re works of art that belong in a gallery. I can only imagine how inadequate people who are used to generic correspondence must feel when they receive them. Come to think of it, I’m making the Morbid Books rejection process sound attractive. So in answer to your question, I give short thrift to anyone who tries to pull a fast one on me, but I respond courteously to anyone who makes a genuine effort.

What are the elements in a piece that make you say, Oh hell yes?

If it’s written by somebody who has paid their dues by complimenting me sincerely and profusely, then I am more likely to look kindly upon it. That’s only half a joke, by the way. Literary organizations propagate the myth that they adhere to impersonal standards, when in fact, they’re social beings who respond to status and personal favor. Let’s be honest about it.

Can you talk about genre? Do you think in terms of poetry/fiction/nonfiction? Or do you have other ways of conceptualizing writing?

It doesn’t really matter. Although I will say one thing, and that’s my objection to the use of “poetry” and “poet” as honorifics. There was a time when poetry was regarded as the highest form of language – they used to say that novelists were failed poets. But now pretty much the opposite is true. People who can’t sustain a novel or short story tend to resort to poetry, because it takes less effort. That’s not to say all poetry is bad, just that 99.9% of it is garbage, and the people writing it couldn’t write a compelling short story or journalistic essay if they tried.

Has anyone ever been offended by the work you publish? If so, what has been your response?

If you want to hide something, hide it in a book! Because there are lots of people who claim to be offended by snippets of material they see on the internet, or stuff I happen to have done socially that they mistake for serious artwork: award-winning noodle dishes, etc. Although the very same activists, who claim that our work poses an imminent threat to people’s safety, rarely go so far as to look behind a paywall or the covers of a publication. This reveals the insincerity of their hysteria. Surely if it was really dangerous, they’d order copies to make sure there was nothing harmful inside, and either report them to the police or destroy them. I mean, there aren’t that many copies, so they could destroy them all if they really thought it was that big of an issue. But obviously there isn’t. It’s all performative outrage. The really spicy stuff isn’t online…

You’re based in London. Are there other magazines there with whom you’ve found an aesthetic affinity?

London was home to some excellent pornographic magazines back in the day – they inspired the punk movement and our own homage, A Void issue 3, the magazine of discipline and pleasure, was based on one guy’s epic collection of dead people’s porn. I’m also a big fan of the Nervemeter, a magazine of social analysis distributed by drug addicts and homeless people.

It sounds like you’ve had some experience talking to editors of other magazines. Can you tell us about your background? How did you come to creating your own magazine for the type of aesthetic you personally are drawn to?

I realize how your readers could get the impression that I’m an obnoxious jerk who has no time for them or anybody else. But having done an MFA myself, I know from being shoved in the direction of literary magazines as a way of achieving validation what a thoroughly dispiriting process it can be trying to get your work recognized. Even if they do accept your work, let’s be honest, hardly anybody reads lit mags except other writers searching for space for their own byline. It’s not like performing a play or being in a band where you come offstage and people slap you on the back and tell you what a good time they had, and you think the hard work paid off. On the contrary, writers go through this incredibly slow, solitary experience of sending their work out to committees of faceless individuals that decide if it’s worthy of inclusion, and then, when one finally accepts your story or poem, months later the editors send you your complimentary copy, and the result is deafening silence. Literally nobody in the world besides you cares – not even the editors themselves, who are often just using the magazine as a stepping stone for their own ambitions. Your work is, sad to say, just filler beneath the masthead where their name appears. You may as well have published it yourself and mailed it to your friends and family. Which is basically what I did. I didn’t expect anybody to read A Void, and still hardly anybody does in the grand scheme of things. Our circulation is still miniscule, in the hundreds rather than thousands. But the people who do read it are passionate about it, and I like to think that the unruly cast I bring together from across the globe feel like we’ve done their work justice by presenting it in a way that doesn’t fit in with other magazines; if you go to the Poetry Library or wherever else it’s stocked alongside other literary journals, it doesn’t blend in, it stands out like a black hole, a portal to a different time and place, because Penny and I spend weeks designing each page so that the form suits the content, and the contents form a cohesive whole that is created with a view to being unlike any other publication currently available. I had and still have very modest ambitions for it, but I knew I was onto something when I released issue 1 in an edition of 200 on our website, and the first person to buy it was Supervert, who I’d interviewed. He was entitled to a free contributor copy anyway, but he bought one because he wanted to support it. That’s when I knew I was onto something, because I respect him a great deal, he has impeccable taste. And he taught me a vital lesson that reverberates through my conscience to this day. The lesson has nothing to do with writing, but something even more important, one all your readers would also benefit from: personal conduct.

Not long after I published A Void issue 1, I went on holiday to New York for the first time, and I didn’t know many people there, so I asked if the enigmatic individual behind Supervert 32C would like to meet me for a drink, fully expecting him to say no, he doesn’t do that kind of thing, and even if he did, he wouldn’t expend that privilege to a charlatan rookie such as myself. He not only accepted the invitation, he directed me to at a restaurant near Union Square, turned up on time, bought me several pints of Guinness on the Supervert company credit card, and showed me a disarming amount of respect, something I had never experienced from anybody in London, including those in the literary scene whom I mistakenly believed were my friends. In doing so, he showed how validation and respect are not zero-sum equations. Be suspicious of anybody who believes that praising you or your work would be detrimental to them, like there’s only a limited amount of positivity in the world, and any they give to you means less for them. That is categorically not true. Or rather, it’s only true if people want it to be, and they’re actually chasing their own tails, destined for a life of bitterness and unfulfillment, because every success they have will come with the suspicion that just like their own praise, none of it is genuine. After spending several years on the outskirts of literary and journalistic scenes, I now know from this shining example – and a few other independent artists with similarly impeccable personal conduct – that there is another way. Mutual admiration is a way more powerful force than petty niggles, selfish insecurities and backhanded compliments. If you like or admire somebody’s work, be open and full-throated in your support, because in a world of diminishing resources, one thing we have an endless supply of is respect. Just make sure the people you give it to deserve it, and see how your life improves when you stop rationing your praise. You can be the biggest douchebag in the world to people whose opinions you don’t care about (which should be most people), but if you make sure the ones you care about know you’re on their side, you will be liberated to be the purest version of yourself, without reservation or compromise. Or as Walt Whitman called it, “Nature without check with original energy.” Isn’t that what we’re all after, really?

If there is a writer out there reading this right now and thinking, Yes, this is the magazine for me, what should they do? How can they make a connection?

Join the Temple of Surrealism! We get no funding or support except from the people who like what we do and support it.

What is your favorite OuLiPo prompt? And why?

It has to be the lipogram, the technique Georges Perec used to write the novel our magazine is named after…

It’s funny you mention that because for a while now the letter “e” on my keyboard has been broken. I have to pound down extra hard on that letter to make it work. I’ve often wondered if the spirit of Perec isn’t secretly guiding me in some way. To be honest, though, my writing tends to be more traditional–character-oriented, narrative-focused. Do you think there are craft techniques from Surrealism that writers of more conventional forms can draw from?

There’s an anecdote from the history of Surrealism I tell to people who are just encountering the movement, which illustrates the point well. Shortly after Breton published The Magnetic Fields and their other experiments with automatic writing in their journal, critics who were suspicious of Surrealism decided to send in some spoofs to see if there was any criteria on which automatic writing could be deciphered. And it turned out there wasn’t. The spoofs made it through. Humbled, Breton realized that the early free-associative texts had become a style that was easy to replicate. After that, he and Paul Eluard released The Immaculate Conception, which was automatic writing within certain constraints: those short texts were more like method acting, where the authors imitated various mental conditions. These texts were much more varied in style, and I would argue more successful. Some were hysterical, others were more deadpan and droll, narrative-based. What we learn from them is that Surrealism isn’t a style, it’s an approach. Most of what I write and publish is narrative and character-based. Most of it appropriates mainstream genres, from the detective novel to the horror story, and yes, I edit them, so maybe they’re not even Surrealist texts in the truest sense of the term. But I tend to propel them with a guiding principle, then allow the narrative to go wherever the language takes it, like riding a bicycle downhill without brakes.

One thing I think people may not realize about the type of work you do is that a lot of it is funny. You mentioned your art installations, which are quite clever. Raymond Queneau’s Exercises in Style is also pretty funny. So is the modern graphic novel adaptation by Matt Madden. Would you say this is true? Obviously, in looking at your journal, “humor” is not the first word that comes to mind. But there is a wry undertone to some of the work. Even the idea of a “surrealist summer camp” is kind of funny. Can you talk about how humor and playfulness figure into your vision?

Absolutely. The joke is my primary unit of expression around which everything else is constructed. Even supposedly serious endeavors like inviting people to spend a week with us in Norway started off as a spoof advert in the magazine that we were brave or foolish enough to make happen. The same goes with my poetry. The idea of charging people for improvised verse seemed ridiculous (and still does), even after my friend Tim, who took the plunge first, told me that it worked. I still couldn’t take it seriously, so I made a sign that said, “Poems, stories, suicide notes and more.” People began asking for the suicide notes, so I created brief narratives for them and collated them into the first Morbid Books publication, hand-typed in an edition of 33 for a gallery in Paris, titled Suicide Notes. The first one I ever wrote is probably the best, and might give you an indication of how automatic writing can be put to any use. It’s pretty much my work in microcosm, and also the piece that generated the bent-spoon logo:

In retrospect, hiring Uri Geller for my 40th birthday party was a mistake. I know when Uri was on Noel’s House Party, I marvelled at his ability to bend spoons with just his mind, and I admit that I rushed out and bought his book, and joined his mailing list, and paid over the odds for a cardboard cut-out of Uri that I kept by our bed for the duration of our marriage. But when he turned up to the barbecue and read my mind, he revealed to the world secrets that I can’t handle being known.

– Suicide Note #1, from Poetry for the Poorly Educated

How do you decide your theme issues?

When I started A Void, I was adamant that I wasn’t going to create a themed publication, because it felt like every other journal had “Myths and Legends” as its theme, and that was usually a good indication that it had run out of ideas. Although since it’s basically my personal journal, I relish the power to be as extreme or devotional towards my interests as I can be. There’s a lot of organizational hassle that comes with running a publisher, even one as chaotic as this one, so I have to make sure the freedom I get in return is worth it. So I took a great deal of satisfaction from turning my literary magazine into a porn mag for issue 3, and became a total megalomaniac for issue 4, which was loosely based on the Jim Jones Peoples Temple inhouse newsletter – although we’d been issuing membership cards inspired by the Church of Satan for a couple of years, so I suppose that idea had been brewing for a while. I guess it’s a form of method acting or meta-fiction, blurring the lines between reality and fantasy, where not only the contents but the entire operation is a projection of my personal desires.

What’s on the horizon for A Void? What is the next theme?

Issue 4 ends where Issue 1 started: a dialogue between myself and Supervert on the nature of transgression. It feels like we’ve gone full circle, an end-point has been reached with almost perfect symmetry like a giant palindrome. Although there will almost certainly be another magazine if I’m still around to publish one. Blueprints are already being drawn up…

Should writers submit work only related to the theme or should they just send something they think is a good fit?

I hardly ever publish something sent off the hoof, especially if the writer isn’t already indoctrinated into my way of seeing the world. Most of the material I discover myself, or I ask somebody to write something specific. I have a short attention span, so you have to grab it and keep it.

When are you open for submissions?

Always and never! It depends who’s asking and what they’re offering.

Got questions for Lev? Drop them in the conversation and he’ll be by to answer them.

That response to submissions may be one of the best things I've ever read 😄

i feel like a secondary school teacher:

very refreshing

extra good marks for analysis of industry

attitude

I don't like maybe all the forms he likes, but i especially like his attitude

terrific rejection letter

so many things to like here check plus